Genji

The year 1008. The Imperial Court of Kyoto. Delicately folded sheets of coloured paper lie gathered on a shelf, carrying the lingering whispers of perfume. Under the muted light of an oil lamp, a lady draws her brush across the page, continuing the tale of Genji, the rise and fall of a prince never destined for the throne. We know almost nothing of her, beyond the name Murasaki Shikibu, and that she is unknowingly creating the modern novel.

-

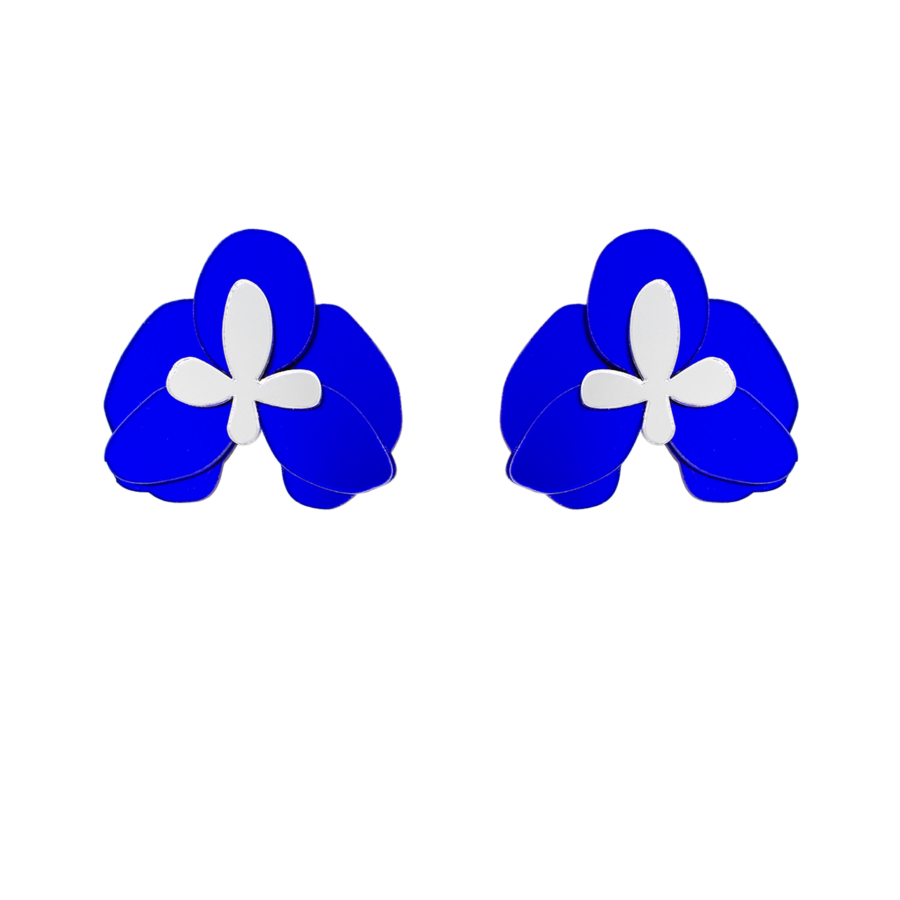

TAMAKI

140,63 €TAMAKI

140,63 € -

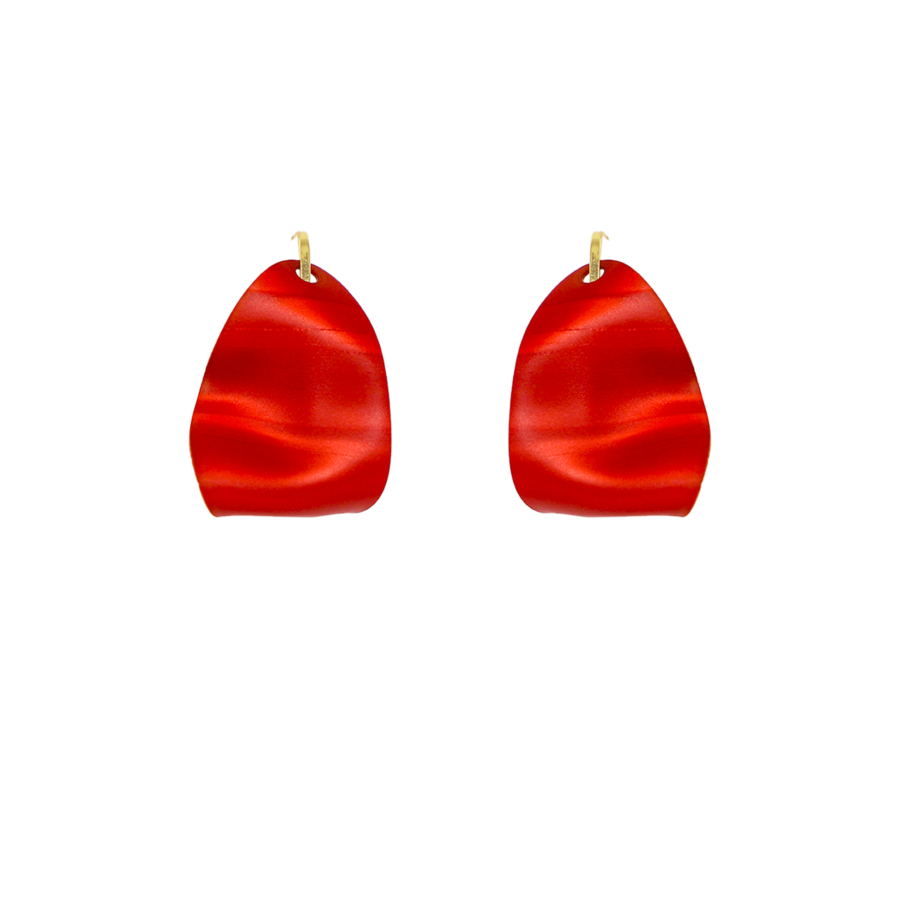

YUGAO

Sold OutYUGAO

Sold Out -

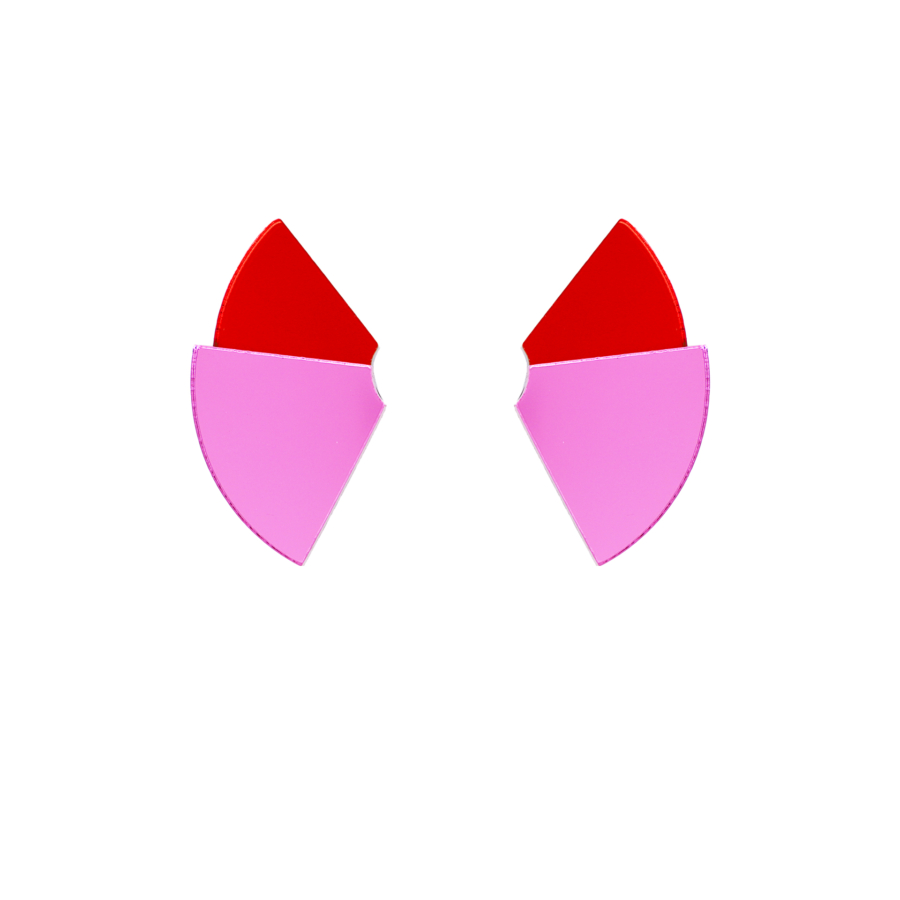

MIST

Sold OutMIST

Sold Out

A chronicle of customs, a family saga, a monumental tableau of a vanished society, one that predates geishas and samurai, Zen gardens and the tea ceremony, haiku, Kabuki theatre, and everything – or almost everything – we now associate with traditional Japan. Rooted in aesthetic values of exquisite refinement and in meticulous codes of conduct, within a world where walls are made of paper and the very notion of solitude scarcely exists, a society that admires women for their capacity to create beauty, and where “a good lover conducts himself with as much elegance at dawn as at any other hour”.

A monumental tableau of a vanished society.

Confined to dimly lit chambers within the palace complex, concealed behind folding screens and swathed in layered robes, their teeth blackened and faces powdered white, the women within communicate with men through letters fastened to the branch of a flowering plum tree. And thus the court glows with poetry devoted to love, to courtship and its careful rituals, to the approach of the beloved, to playful encounters in shadowed chambers, and to endings uncertain yet ever passionate, shaped by affection, promises and betrayals.

-

LETTERS

85,94 €LETTERS

85,94 €

-

STROKES

70,31 €STROKES

70,31 €

A meditation on the fragility of desire and fleeting beauty.

With a gaze capable of revealing both the protocol of courtly aristocracy and the exquisite poetics of the Heian period – the detail of a sleeve, a stroke of calligraphy, a texture shaped to mirror a mood – The Tale of Genji also offers a meditation on the impermanence and fragility of desire, on the melancholy inherent in fleeting beauty, which opens a space between what is shown and what remains concealed, between what is suggested and what is left unsaid, upon the perpetual threshold of insinuation. Behind a curtain, a woman watches as a man steps inside. And Murasaki writes: “Instinctively, though she knew perfectly well he could not see her, she smoothed her hair with her hand”.

-

MOON

85,94 €MOON

85,94 €

-

TWILIGHT

70,31 €TWILIGHT

70,31 € -

TRANSITION

125,00 €TRANSITION

125,00 € -

POEM

109,38 €POEM

109,38 €

-

SILK

101,56 €SILK

101,56 €

This vaporous spectrum of whispers and veiled gestures, of half-kept secrets, and the gentle melancholy of the eight hundred poems it contains permeate the human soul, expressing the beauty of that violet-hued world of countless characters, with all the unrest and agitation of their hearts. From this world, we draw the collection, where each jewel takes its place like a chapter within the tale.

A vaporous spectrum of whispers and veiled gestures, of half-kept secrets.

-

FUJI NO URABA

125,00 €FUJI NO URABA

125,00 € -

CONSOLATION

117,19 €CONSOLATION

117,19 € -

RED PLUM

85,94 €RED PLUM

85,94 €

-

FAN

93,75 €FAN

93,75 €

The white, delicate pieces of the opening sequence, evoking the inner layers of kimonos, pale blossoms, the translucent paper of letters, and the soft light filtering through folding screens, give way to the blue and silver creations of the central chapter, deeper and more introspective, before culminating in an outburst of pinks and reds symbolising the wound of our ill-fated prince. All of it is crafted in methacrylate, allowing us to shape transparency and colour with precision, creating earrings and necklaces that respond to light and movement, much like the emotions of its characters.

A peerless work whose legacy remains alive today.

-

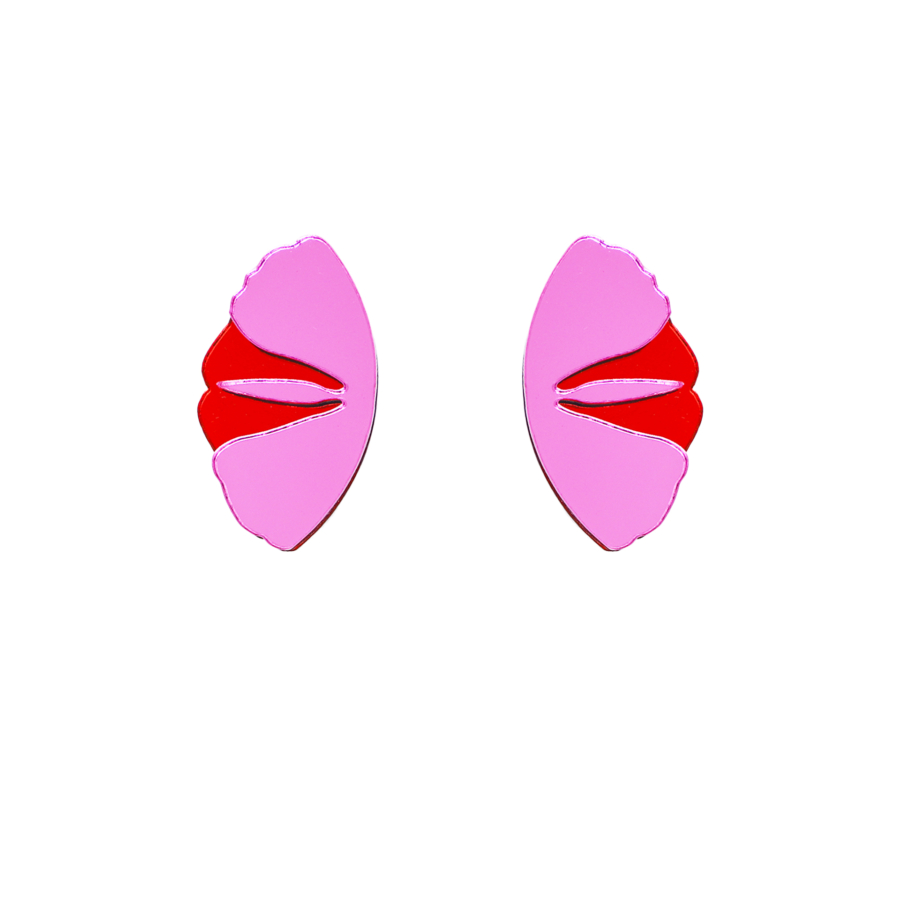

FLUTTER

85,94 €FLUTTER

85,94 €

Here we reimagine a peerless work whose legacy remains alive today. That invites us to embrace the beautiful fragility of existence and reminds us that there is no ascent without decline, nor love without sorrow. That deepens our understanding of human feeling and shows us how to see beauty in uncertainty, even in the cruellest decay. Woven with the language of dreams. That begins in the tone of a folktale and, two thousand pages later, seems to have travelled through the entire history of literature. So sublime, so sophisticated, and “so beautiful it seems not meant to endure in this world”.